RECA | RE-TUNING CINEMA IN AFRICA

|

Well, I would like to say I will save you all the history and science terminology of what popcorn is and all the jargon that explains why it pops, but I won’t. You need to understand the correlation between popcorn and movies. We all have been to the movies a couple of times, and probably never miss to get a packet of popcorn and a drink as we go in to treat ourselves to a moment of imagination, and wonder as we travel through someone else’s mind and simply allow ourselves to be entertained. Now, there are two kinds of popcorn flakes –the Butterfly flakes, which are irregularly shaped pieces with wings, considered to have a more pleasant mouth feel and is generally used for movie and everyday snacking popcorn: and the Mushroom flakes, which take on a more ball shape, making them less fragile and often used for prepackaged popcorn and confectionery like caramel corn. Why Is Popcorn Such A Popular Snack At The Movies? It’s buttered, it’s salted, it’s plain but it’s always hot and delicious (or it should be) but why do we all hanker for popcorn at the movies, and pop it when we watch at home? Popcorn itself has been around 8,000 years since corn was first cultivated, but it’s been a movie theatre staple for far less time. As far as the talking pictures are concerned, popcorn was a big no-no at the first theatres. Movie theatres wanted nothing to do with popcorn because they were trying to duplicate what was done in real theatres. They had beautiful carpets and rugs and didn’t want popcorn being ground into it. Popcorn was basically the food of the streets, and as such, had no place in hoity-toity movie theatres. Plus when there wasn’t sound playing during the days of silent films, the crunch of your neighbour is even more annoying. Eventually, movies added sound, and the movie theatre industry started to broaden its horizons. When the Great Depression hit, audiences flooded movie theatres seeking an escape from the everyday blues. And there was popcorn, cheap, mobile and tasty. At first, people would just walk in with their popcorn purchased on the street, despite the protestations of theatre workers. Movie theatre owners finally bowed under the pressure from customers who were going to eat popcorn at the movies whether they liked it or not, and started allowing vendors to shill their snacks in the lobby of the street or right outside for a fee. Things really kicked into high gear during World War II, as wartime rations severely limited the competition from other snacks that required sugar. By the time the war was over, popcorn was firmly entrenched in the hearts of movie lovers everywhere. Once microwaves started popping up in homes later in the 20th century, popcorn was there to stake its claim as the proper snack companion to living room theatres as well. For some, the movie-going experience is simply incomplete without a bucket of buttery yellow popcorn. The tie is not only a personal and cultural connection, but it’s also actually an economic one as well. Popcorn pulled movie theatres from bankruptcy during the Great Depression and it still accounts for as much as half of the profit generated by movie theatres today more so than the actual ticket price, which has to be shared with the movie studios distributors. By charging that outrageous and frankly insane mark-up we pay at the concessions, the movie theatre can keep ticket prices lower and make their profit selling snacks and treats. Ultimately it is this little puff of air and starch that is responsible for keeping movies in business. For without popcorn, there simply would be no theatres, and perhaps no movies at least not the way we know them. Whether you partake or not, know that this simple ancient snack help make film and film making possible Source: Smithsonian Magazine, Film Maker IQ, Consumerist

0 Comments

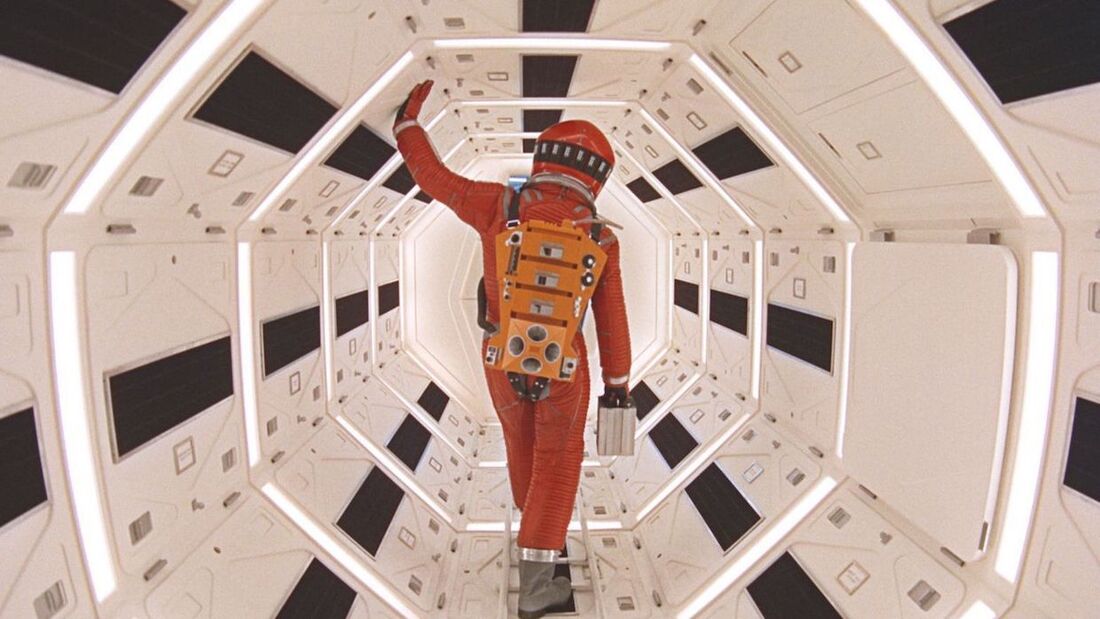

The concept of symmetry sounds simple and familiar, yet symmetry is far more complex and difficult to apply in practice than one might think. The visual power of symmetry is so great that filmmakers often avoid or are advised against using symmetrical picture compositions. And this is not so odd, for if symmetry is used randomly and thoughtlessly, one runs the risk of creating visual disturbances in the narrative of the film. On the other hand, the filmmakers who master the art of symmetry wield a powerful visual aid capable of communicating complex meanings that cannot otherwise be conveyed visually. Source: Variety Magazine The film “The Great Budapest Hotel” is an example of symmetry in the work of Wes Anderson, a signature similar to the one in Stanley Kubrick’s films. Different authors will call it “one-point perspective”, “symmetrical composition” or “centred vision”, and many times aren’t agreeing on the definition and how it works to translate one idea. Whatever it is, it’s a unique tool in the cinematography of different names in the industry and used for different purposes in most of their films. Source: Filmmaker Magazine Stanley Kubrick seemed obsessed with the use of symmetry in his films. Probably due to the fact that many of Kubrick’s films are, one way or another, violent, different authors have associated that search for symmetry with the desire to create a psychological reaction in the audience, like the one felt when viewing the long corridor sequences in “The Shining”. The effect is so intense that even when nothing is happening, viewers tend to expect something to happen. Source: TheUnredacted Kubrick’s technique may well be associated with unsettling moments, but it is not be limited to that, as the cinematography of Wes Anderson reveals. The difference is that in many of these films and sequences, the one-point perspective or symmetry is the basis for a humorous take instead of a horror moment. So, although Anderson is paying homage to Kubrick’s work, he is using the same language in completely different ways. ADVICE ON THE USE OF SYMMETRY The following are a number of approaches to symmetry in film. Symmetry is a very obvious form of composition, which of course offers opportunities but at the same time can cause a situation to seem artificial, stilted, and thus shatter the illusion of the fiction. This is possibly the reason that a lot of filmmakers try to avoid symmetry. If this is a concern I think that sophisticated use of symmetry could circumvent such problems. And whatever the approach, my advice is as follows: Rather than accentuating insignificant events in the film, it is important to emphasize those that are important at the right time. In addition, it is important to remember that like any other filming device the effect of symmetry is weakened by frequent use. source: ProVideocoalition, Louis Thonsgard

|

Various AuthorsCinephiles that love writing about film ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed